|

|

||

|

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Province of British Columbia through the Ministry of Healthy Living and Sport, and the assistance of the British Columbia Museums Association.

|

Rosemarie Stodola: Always Embracing the Future

|

|

|

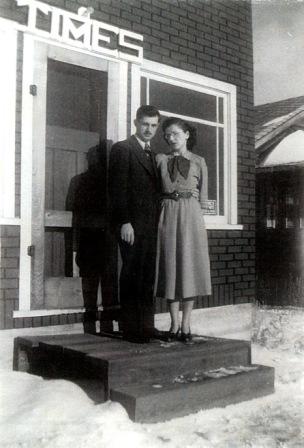

Rosemarie, 1944 |

by Maureen Parriott

A newspaper is the beating heart of a community. But Osoyoos was 'heartless' until a young couple not long removed from their families' farms gazed out a bus window coming down Anarchist Mountain and saw a lake and a tiny settlement below. The year was 1946. They were twenty and twenty-two.

Rosemarie Werbisky Stodola was destined to be a teacher. Not long after her birth in 1925, she began demonstrating her calling by lining up her dolls for instruction. At seventeen, she left her small Polish farming community of St. Michaels, Alberta, for normal school (as teachers' colleges were then known), and only a few months later, for her first teaching assignment. Hers was one of many towns dotting the Prairies around Edmonton that had been founded at the turn of the century by Poles, Germans, and Ukrainians bold enough to seek a better life. Her father, Felix Werbisky, had fled an abusive overlord in Poland at sixteen, taught himself English, worked on railroads and in mines, bought a farm, and eventually became a member of the St. Michaels school board. Her mother, Xenia Kucy, came to Canada as a child with parents who had first emigrated from Poland to Hawaii in the 1800s to manage a sugar plantation. Disillusioned by the oppression they encountered there, and lured by the dream of owning land, they found their way to Alberta in 1905. Felix and Xenia had four children, all of whom graduated from high school – a rarity then – two of whom followed Rosemarie into teaching.

Rosemarie was posted first to St. Paul, and then to Lamont, two more small Polish farming communities. She had a several boys in her class the same age as she was, and definitely bigger. Maintaining order was not a problem. "I just lined them up and gave them the strap," she says matter-of-factly.

|

|

|

Rosemarie and Stan, 1946 |

Stan Stodola, eldest brother of numerous Stodola siblings attending the Lamont school, dropped by in search of a younger brother one day, and instantly launched a stealth courtship. His suit was severely tested, however. "We teachers were the stars in these small towns," Rosemarie remembers fondly. "We were usually in no hurry to pick one of the farm boys buzzing around." Stan jokes that it was only his unwavering persistence that finally won her over. They wed when she was twenty. A month later they were off to Grand Forks, BC, where Rosemary had accepted another position.

They wound up on the bus heading down the Anarchist switchbacks after Rosemarie had taught in Grand Forks for a year while Stan worked in the bush. They had decided to see what Vancouver might offer during her summer holidays, but after a few days in the big city, reversed course. At a stopover in Oliver while heading back to Grand Forks, they attended a ballgame where a bleacher-mate extolled the virtues of Osoyoos as the "next big thing." Stan made another instant decision. Just as Rosemarie had always known she wanted to be a teacher, he had always known he wanted to be a newspaperman. He had no background, no training, only the memory of the handwritten Polish-language newspapers that had circulated from home to home when he was a child that had fired his passion to communicate. He had already been cajoled into writing a few pieces for the Grand Forks paper, so he had no doubts about his destiny.

They discovered that the Okanagan Board of Trade supported establishing a newspaper in Osoyoos. Rosemarie immediately found a teaching job, Stan took orchard work and odd jobs, and they set about learning to be journalists. They named their weekly the Osoyoos Times.

|

|

Stan and Rosemarie, Osoyoos, 1948 |

The heart of the community began beating in 1947. Stan collected news and wrote articles, Rosemarie proofread, and they both learned about business. They shipped their copy by bus to the Penticton Herald for printing, and got their papers back the same way. Stan picked up the 250 or so copies on his bicycle, took them to their cubbyhole of an office where they hand-addressed each six-pager, and then took them to the post office to mail to their subscribers. A year's subscription was $2.00. They lived above the shop – still in the same Main Street location 62 years later – and Rosemarie became ever more deeply involved.

The oven-like summers were difficult for Rosemarie to adjust to in the beginning, especially when she was expecting their first baby. She and Stan still laugh about how often she trotted downstairs to stand under a hose mounted in the backyard for relief from the heat.

They bought their own well-used press and linotype machine in 1950, just as farming, orcharding and tourism started to boom in Osoyoos. Both learned to type on the clattering, cranky linotype, which formed letters from a pot of hot lead. Rosemarie still remembers the agony of one day spilling the lead down her leg and the months it took to recuperate. They retired the old machines when they embraced computers in the mid-'70s, ahead of many other small community papers' conversion to modern technology.

As their little ones arrived – Bernard in 1949, Chris in 1951, Sherrie in 1954 – Rosemarie tended them in the shop. They often napped to the soothing rhythm of the press ka-thunking away on printing day. She had stopped teaching full-time as the children and the business grew, but continued catechism instruction for the Catholic church and substitute taught occasionally.

Rosemarie and Stan took their first long trip away from the paper when they attended a press convention in Nova Scotia in 1961. It inspired Rosemarie to start writing her own column, "The House on the Hill." The title referred to their home overlooking Lake Osoyoos. In the column, she shared her impressions of the people and places they encountered on that and succeeding trips, first around the country, later around the world. Ever the teacher, she sought to fire her readers' imaginations and expand their worlds. She also wrote about local events, family life, and community issues.

Stan, meanwhile, earned a reputation as an outspoken editorial-writer and booster of all things Osoyoos. He served on the Town Council, Board of Trade, school board, and regional district, as well as other community-betterment organizations.

|

|

Stan and Rosemarie, Osoyoos, 2001 Photo Credits: Don Chadderton |

Rosemarie stayed serenely in the background, not because she didn't have strong, well-articulated convictions, but because she was busy devoting herself to her own causes. She and several friends organized the Osoyoos Museum Society to preserve the heritage of the young community and its First Nations predecessors. They started with an arrowhead collection lodged in the town hall. They met weekly to create exhibits, paint picture frames, and preserve artifacts. She and her fellow volunteers launched the annual Osoyoos Folk Festival, featuring musical groups from across western Canada. She was one of several Osoyoos teachers, nurses, secretaries and homemakers who organized literacy classes for immigrant women. There were as many as twenty-five teacher-student pairs at the height of the program. "Some of the students were from cultures that did not value women the same way as Canadians do," she remembers. "One of my deepest satisfactions came from witnessing the changes in their view of themselves as they learned to read and to gain a greater awareness of their rights in their new country."

|

|

Rosemarie and Stan, 2005 |

Rosemarie and Stan finally decided to retire in 1986, after forty years of 'Mom and Pop' journalism. They sold the paper to son Chris and his partners. He subsequently bought out the partners, and the Osoyoos Times was once again a totally Stodola venture. Under his even-handed management, it continues to be central to the town's sense of identity – its heart.

Today, despite health problems that limit her travel, Rosemarie remains deeply engaged with her three children, seven grandchildren and everything that occurs in Osoyoos. Nothing escapes her keen gaze, and her total recall of the who, what, when, where and why of the community's political and social history makes her a fount of wisdom. As well, she says, "We feel content with the part we played in helping so many wonderful dreams come true."

If you were to ask Rosemarie to define destiny, what do you think she would say? That destiny is what happens to you? Or that it's what happens when you open you arms wide and embrace the unknown?